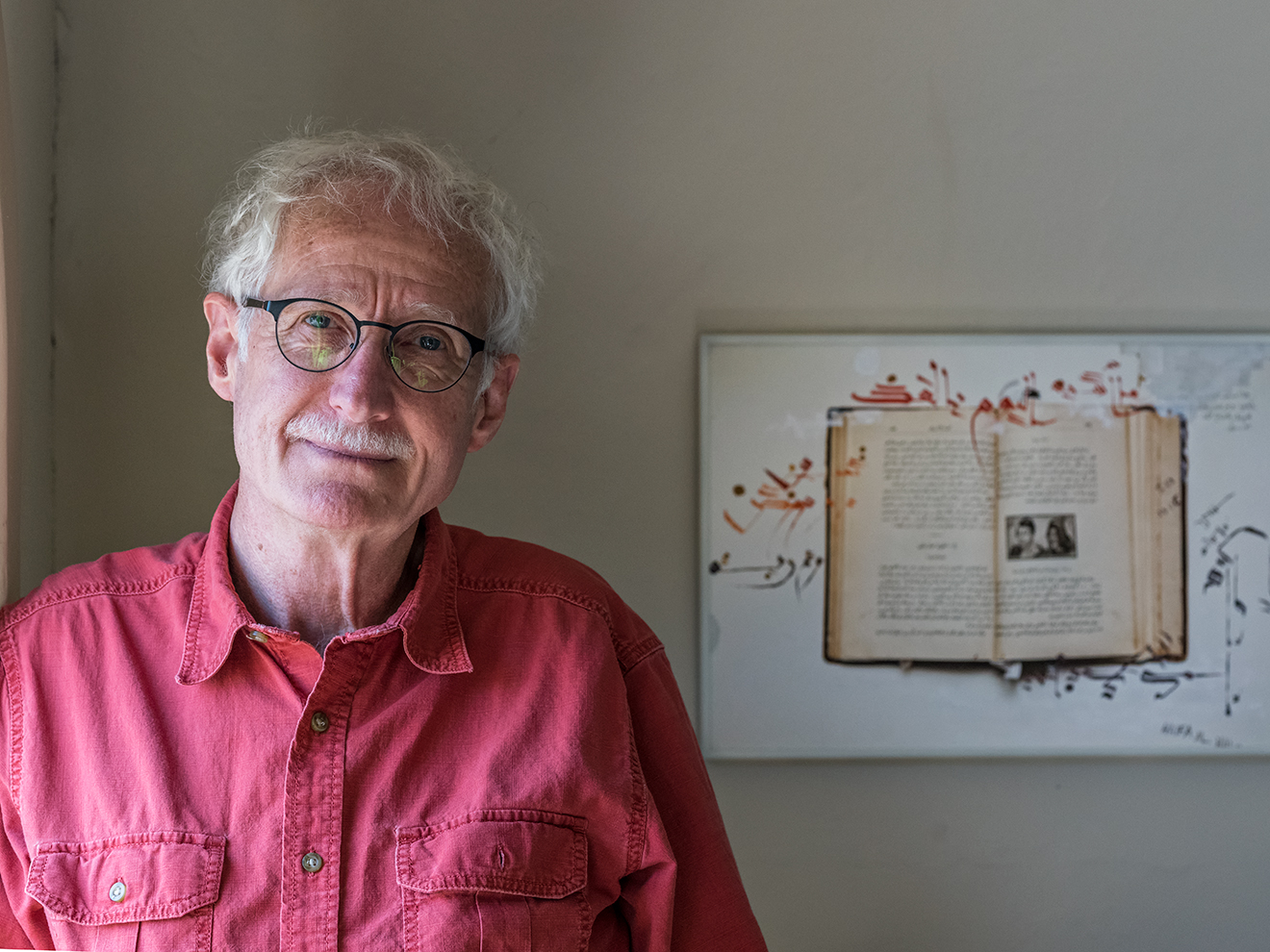

A portrait of an Iraqi refugee’s family propelled award-winning photographer Jim Lommasson on a mission: to ensure that Americans hear the stories of Iraqi and Syrian refugees and understand what it feels like to flee one’s homeland.

When Lommasson had his aha! moment, he was working on a book project, “Exit Wounds: Soldiers’ Stories – Life After Iraq and Afghanistan,” about U.S. soldiers returning from those war zones. He was toying with the idea of following that book with portraits of and interviews with Iraqi refugees.

That’s when he met an Iraqi woman, and interviewed her about what it meant to leave home.

“I was in her apartment, and noticed she had a family portrait. I asked her about that, and she said when she left Iraq, she left with her daughters, and took with her a picture of her family and her Qur’an when she went to a refugee camp,” recalls Lommasson, winner of the Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize from Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies.

That got Lommasson wondering about what Iraqi refugees decide to take with them when they leave their homeland forever. It prompted him to think about the important stories that reflect those choices, and how they could provide a captivating forum for discussing Iraqi refugees’ experiences.

The woman asked Lommasson to photograph the family portrait to duplicate it, and when he returned to her apartment to give it to her, he asked her to write her story directly on the print.

“Once she did that writing, that was my aha! moment. I realized it was so much more effective and honest and direct to have her write on the photo than if I did a photograph and interview,” he says.

And so his latest project, “What We Carried: Fragments from the Cradle of Civilization,” was born. Since then, the project has been exhibited across the country and featured in numerous newspapers and radio stations, large and small, in the U.S.and in the Middle East, including NPR, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, The Daily Star (Lebanon), Alhurra TV (Iraq), and Karbala TV (Iraq), Oregon Public Broadcasting, and several local newspapers and TV news stations.

On display at the Beaverton City Hall until Dec. 31 as part of the “We The People” exhibit are photos from Lommasson’s project that focus on leaving friends behind, possibly forever. One is a photo of a young refugee’s Hello Kitty book inscribed with good-bye messages from friends. Another is a girl’s poem about the bomb that changed her life. Yet another is a ceramic piece—a typical souvenir from a gift shop depicting well-known monuments—on which the words “I (heart) Iraq” were inscribed by friends. Another depicts a domino set a refugee played with his friends when he was growing up. “Keep this and remember us,” was the message, says Lommasson.

The documentarian first shared his project with the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Mich., where many Iraqis settled and found work in the auto manufacturing industry. The museum has taken the exhibit to Houston, Atlanta, and other cities.

“What We Carried: Fragments from Iraq and Syria” will show at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, May 28-Sept. 3, 2019. An estimated 500,000 visitors are expected to view the exhibit there.

Since the 2016 crisis in Syria, Lommasson has expanded his project to include Syrian refugees .

But “What We Carried” and the attention it has attracted isn’t about Lommasson, developing his resume, or amassing an impressive list of media credits, he says.

“What I hope is that when viewers look at the photos, they will start wondering what they would take if they had to leave, right away, under the cover of darkness. I want people to have empathy and compassion for these refugees. I want them to realize that these refugees leave behind their homes, their jobs, their culture, their friends, and their history,” he says.

He also wants viewers to cast aside the stereotypes about refugees they see on TV. He hopes they reject stereotypes of desperate, dirty, people fleeing, and open their eyes and ears, as Lommasson himself as done, to see a different reality.

“We don’t realize that before these people left their homes under duress, many were civil servants, teachers, doctors, and engineers,” he says. “We realize that we would look just as tired and desperate as refugees if we had to flee our homes because of violence or a natural disaster.”

And Lommasson hopes that when people study these photos—of candle holders, tea cups, carpets, and even Barbie dolls—they’ll be better able to relate to the plight of these refugees.

“It’s a way of learning that we’re not that different. People in the Mideast have been so demonized. Hopefully this is a bridge-building experience,” he says.

Throughout Lommasson’s bridge-building mission, the refugees have told him that he’s the first American “to give them the time of day,” he says. And for that reason, “What We Carried” has sparked both gratitude and tears from the refugees.

“Sometimes when I go back to the refugee’s home, a father might be reading the finished piece out loud and I look around the room and see that the grandmother and children are in tears. Eventually I’m in tears, too,” he says. In some ways, his tears are happy: He is successfully serving as a conduit for these important stories.

However, for an artist like Lommasson, the process isn’t just about being a conduit. It’s also about searching, listening, and learning from his research–a process that inspires and drives him to continue creating. He says that each project is “like earning another college degree in a new subject.”

“I learn so much,” he says. “Photography has give me a backstage pass to the world.”

_________

Lommasson has extended his “What We Carried” work to survivors of Holocaust and genocide. The project, called “Stories of Survival: Object Image, Memory” is sponsored by the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center, Skokie, IL. and is a national exhibit now at the museum until Jan. 13. Learn more about this project from here.