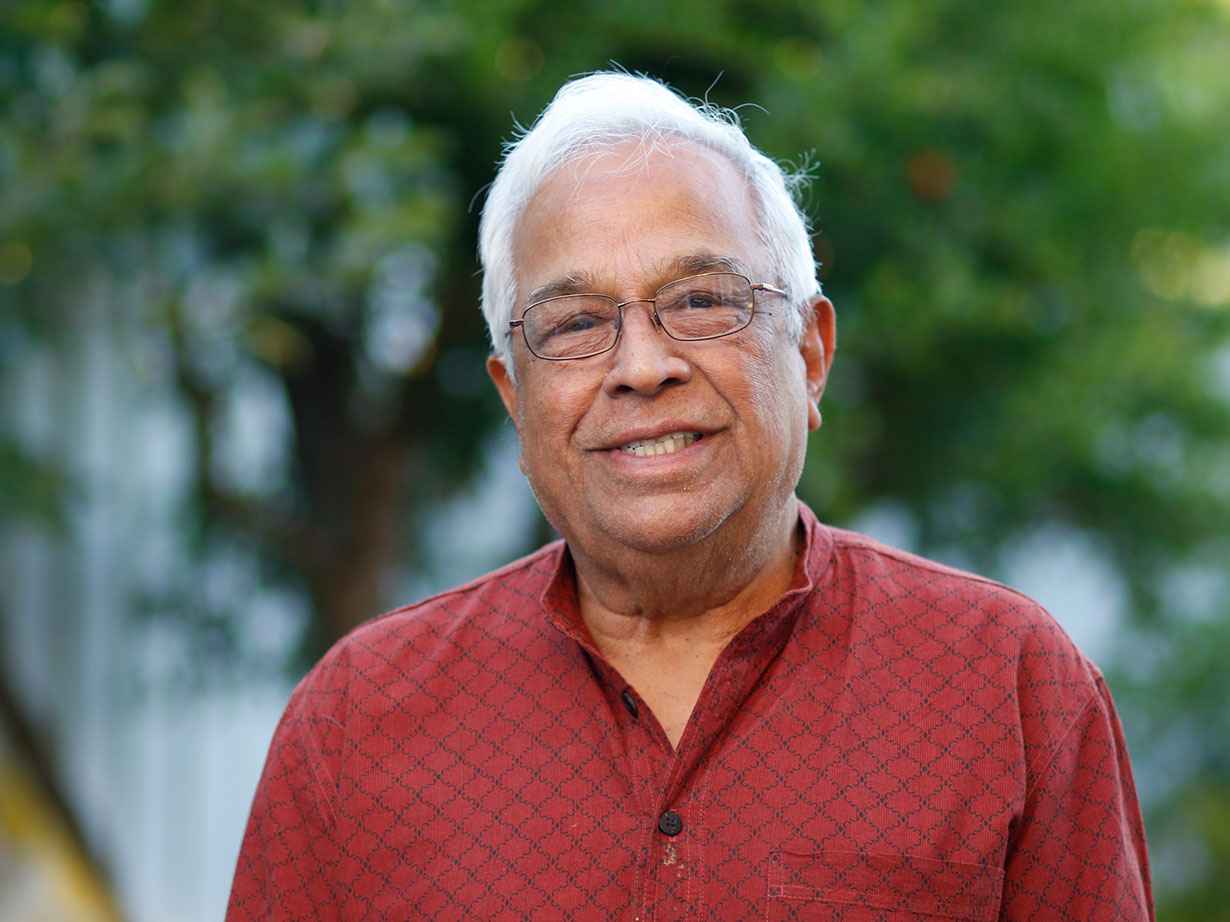

Hard work and a clear sense of who he is have created a lifetime full of satisfaction for Balasubramaniyan Iyer, who says, “(For me) every day is an auspicious day.”

Bala Iyer, who uses a shortened Americanized version of his name, was born in 1939 in Jabalpur in central India.

The family had moved there from the Madras Presidency (now called Tamil Nadu or Tamil State) in South India when his father got a clerical job with the national railway system. Such clerical jobs became plentiful, though not highly paid, throughout the country as Britain established a widespread rail system to support its control of the subcontinent. These railway jobs were valued because they were stable and provided a reliable income to many Indian families.

Iyer’s home was in a quiet, insular setting with little exposure to the outside world, although he would see British officers on the streets at times. The family preserved their South Indian roots — continuing to eat their traditional foods, speaking the South Indian language, Tamil, and listening to music. He remembers that his father and two older sisters often sang traditional Carnatic music from South India.

“It was a fantastic place to grow up,” Iyer says. “I knew everyone in town. A group of us, all friends, would walk about a mile to school together.”

Although religious differences, especially between Hindus and Muslims, would soon tear the country apart, Iyer says the children in his town were mostly unaware of the increasing strife.

“We were about 50% Hindu, 50% Muslim in our town,” he says. “But we (children) had no concept about being from different religions.”

A Working Schoolboy

A second grader at the time, Iyer remembers the ceremony at school on August 15, 1947, when India gained independence after two centuries of British rule. Partition divided the nation into India and Pakistan, a strategy designed to accommodate tensions between Hindus and Muslims.

Partition led to great upheavals throughout the subcontinent, with many Muslims moving north to Pakistan and many Hindus heading south to be within the new boundaries of India. Iyer remembers food rationing and hearing of recurring Hindu-Muslim riots in larger cities every summer.

None of Iyer’s own Muslim friends opted to leave for Pakistan, but he made new friends with some Hindu families who moved in from the western Punjab area after it became part of Pakistan.

“Around that time,” he says, “I learned Punjabi from a classmate just because I like learning languages.”

Because the family was not wealthy and Iyer was the only boy, he had to work, even as a child, in order to help with expenses. His after-school jobs included working in a laundry, running errands for a garage and tutoring the sons of local business owners.

“This showed me what the real world looks like,” he comments.

One benefit of his tutoring jobs was receiving extra rations of sugar and grains that he could contribute to his family as part of his pay.

While in high school, he spent one summer vacation working with one of his teachers to write several sections of a textbook in physics and chemistry. He was listed as a contributor in the published work.

As soon as he graduated from high school in 1957, Iyer began making plans to finish a college education as soon as possible so as to start working and supporting the family.

He considered a three-year degree at a polytechnic (vocational) school in town, but when he got a scholarship that enabled him to pursue a four-year degree in engineering, he chose that instead.

He attended Jabalpur Engineering College, where he enjoyed meeting fellow students from all over India. For a time, he considered studying medicine. Then he accompanied a friend to visit the dissection lab.

“I decided then and there that was not for me,” Iyer remembers.

He earned an honors degree, which allowed a student to take extra credits, in 1963.

“It was like having a major in mechanical engineering and a minor in electrical engineering,” he explains.

He began work as a trainee in nuclear engineering at Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in Mumbai (formerly Bombay). This was a very competitive position at the time since India was beginning to develop its own atomic bomb. He earned 400 rupees a month, the equivalent of about $6 in today’s economy, and lived inexpensively in a hostel.

“But I had few expenses,” Iyer remembers. “I lived like a king!”

However, he soon moved to Mahindra and Mahindra, a company where he received excellent training in all aspects of auto production.

“It was a fantastic experience,” Iyer recalls. “I learned to operate every tool and also learned accounting and other management skills. I loved learning it all!”

After 18 months of training, he was hired as a junior engineer for the company.

“At that time, I had no expectation of going out of India,” he says. “I simply planned to work to support my family.”

Going to the U.S. to Get Ahead

However, one of his fellow trainees was planning to go to the United States to graduate school and encouraged Iyer to consider it, too.

“He told me I was wasting my time in India,” Iyer says. “Getting a master’s degree in India took two years and lots of money, but in the U.S. I could get one in a year.”

His mother was reluctant to have him leave the country but his father encouraged him to do what he wanted, so Iyer applied to four universities in the U.S. and was accepted to all of them. He received a teaching assistantship at the University of California, Berkeley, where he planned to get a master’s of science (M.S.) in mechanical engineering.

So, in September 1965, carrying just a single suitcase, a letter of admission to Berkeley and $5, Iyer boarded a plane for the first time, flying from Bombay to San Francisco. He deliberately arrived a couple of days after classes had already started so as not to waste any money while waiting for the term to begin.

He had to figure out how to get to Berkeley and quickly found that people in the U.S. were friendly about giving directions. He had arranged to meet the son of a neighbor from India in Oakland but was not able to stay with him. However, the man’s landlady let him sleep in her office for one night.

The next day, Iyer registered for classes and once more encountered U.S. friendliness when the foreign student advisor gave him a personal check for $100 so he could open a bank account and receive his loan from the university.

As he stood on the street near International House on campus, he had yet one more piece of luck when he met another Indian man who was looking for an apartment. The two found an apartment together.

“Within 24 hours I had the bank account, the loan and a place to live,” says Iyer. “It was all pure luck. Good karma.”

Life As a Foreign Student

Iyer held an F-1 student visa, which allowed him to complete his studies and then work for up to 18 months in his field before returning to India. His first priority was to get good grades and, at the same time, to work as much as possible.

Like most of the Indian students, he had borrowed money to come to the U.S. and needed to repay those loans. His teaching assistantship allowed him to work up to 20 hours a week. He also worked off-campus in an informal arrangement for a man who ran a small shop producing electrical cables; many of the workers manually assembling wires into cables in his shop were Indian graduate students.

“In those days, a dollar went a long way so we were relatively well-off,” explains Iyer. “We found that our Indian education had prepared us well, so we could easily compete with anyone else in our academic classes. I finished the M.S. within two semesters and was ready to find a job where I could put in my additional 18 months of employment.”

Around this time, Iyer took a shortened Americanized version of his name, calling himself Bala Iyer, because people often had trouble pronouncing his name. As had happened to immigrants from other parts of the world throughout U.S. history, such Americanization of names was not unusual for Asian immigrants. People in the U.S. would claim to be unable to understand or pronounce people’s given names and immigrants would give up their names in order to be more accepted in the new country.

In the early 1960s, an overwhelming majority (84%) of immigrants to the U.S. were of European origin, with 6% from Mexico and fewer than 4% each from Asia and Latin America. However, immigration rules were about to change. In October 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The new regulations, heavily influenced by the civil rights movement in the U.S. at the time, were promoted as ending race as a criteria for immigration and focusing, instead, on the contribution each immigrant would make to the country. The 1965 act ended the old system of quotas based on national origin and gave preference to skilled workers and to reuniting families. In practice, the new law had an unintended effect of increasing immigration from areas other than northern Europe, and, in particular, led to an influx of skilled professionals from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Right after earning his M.S. in mechanical engineering, Iyer got a job at Dow Chemical.

“The job was interesting but I didn’t last long,” he remembers. “My supervisor there had a significant bias against Indians. He would make remarks like, ‘You Indians come and take our jobs.’ So I resigned and started working at IBM as an associate engineer in Data Storage Products, an excellent job that suited me.”

In 1966 in the Bay Area, Indian food and amenities were hard to find.

“There were probably only about 1,000 Indians in the area then,” says Iyer, “and just one store we knew of in San Francisco that had Indian spices, so we would make the long trip there. But the Sikh farmers from Stockton would come and buy up all the spices.”

His comment refers to the fact that, up to that time, the most numerous immigrants from India had been Sikh farmers, many of whom worked as agricultural workers in the Sacramento Valley. Their Sikh Temple in Stockton was one of the first religious centers for Indians in the United States.

Iyer had always helped his mother with the household chores, which was good training, he claims.

“In California, I would improvise,” Iyer says, “cooking rice and vegetables and using local peppers to get some spicy flavors. I had to learn a lot, but learning new things is good.”

He would use a friend’s car to get around and, later, bought his own used car. Eventually he found an Indian family and rented a room from them.

“Everything worked out. I am one of the luckiest people on earth,” he says again.

Building Family and Community

In 1968 Iyer went home for the first time and got married in New Delhi.

“My mother had already picked out a girl for me to marry,” he explains. “And for me, what she says, goes. I always had nothing but respect for her; she had the skill of making things happen.”

His wife, Sushila Iyer, is from the same background as he, a Tamil Brahmin; both families are originally from South India.

As immigrants often do, the Iyers wove their own safety net out of personal connections. Stepping off the plane to join her new husband that first day in the U.S., Sushila introduced her husband to a fellow passenger she had just met, a young man also from India, who needed a ride to his new apartment. The young couple used part of their first day together in the U.S. to drive him there.

For their first several months in the U.S., the Iyers lived with another Indian family and, while her husband was at work, Sushila learned how to shop and manage a household in the new country by pitching in to help her friend. They would find basic spices in local grocery stores and adapt their recipes as needed, following the vegetarian menu they were accustomed to.

During the next several decades, an expatriate Indian community developed in the Bay Area. Specialty grocery stores began to appear and a few priests operated small temples from their homes. In 1976, the Iyers participated in the groundbreaking for the first Hindu temple in the area, in Livermore.

The growth of the Indian population in Northern California reflected a nationwide trend. Statistics show that the population of Indians in the U.S. has grown from 12,000 in the early 1960s to 2.4 million in 2015. In 2013, India, along with China, became the two top sources of new immigrants to the country, surpassing numbers of newcomers from Mexico.

“I saw the whole thing happen — the influx of Indians,” says Iyer. “They tended to be highly educated and disciplined, focused, and willing to work hard.”

Although they had originally planned to stay in the U.S. only a couple of years while Iyer got his education, both Iyer and his wife were able to get green cards, which allowed them to live and work permanently in the U.S. They bought their own home, had two sons and now have five grandchildren.

“Now my friends are here, my life is here,” notes Sushila Iyer. “I am very Indian still, but this has become my place.”

The Changing Workplace

As the Bay Area diversified, Iyer’s professional life reflected the changing workplace.

In 1967, IBM was “a coat and tie company,” Iyer says, with good facilities and excellent benefits. He recalls that he was “probably one of the first 50 nonwhites hired there”.

“The management was always white men,” he notes. “White was always preferred over nonwhite for any given job — although there was no overt discrimination and I would like to believe I was respected. But there was no question I had to prove my skill and my knowledge every day, more so than my white peers. I had to work harder to get the same American dream. I had to work 10 plus hours a day; the number of hours was always out of your control.”

Change does come for immigrants in the United States, he observes, but not until they see it happen for their children who are born in the U.S.

“My children, raised in the U.S. culture, have a different culture than I have, and they have many more opportunities,” Iyer says. “Now you see many Indian CEOs.”

Statistics bear him out. In 2020, 40% of second-generation immigrants work in professional management and related jobs.

Even while working, Iyer pursued his interest in learning about different places, and the family took many trips in motor homes to visit national parks across the U.S. After his retirement, he and his wife bought an RV and did a cross country trip.

“I am an optimist and also a realist,” says Iyer. “What I have is a wonderful conglomeration of all cultures. I have been very fortunate to work with people from many different places and backgrounds and all these experiences have molded me. I can put myself into the mind of many men. I am a very lucky person.”

13 thoughts on “Equal Parts Optimism, Realism”

I loved reading this article. I hope someday my uncle will write more about his childhood and growing up with his siblings and parents, so that I can get some insight into my mom’s childhood.

Hello Renu,How are you?heard you were not well.Hope this year is different and things come to normal.Thanks for your nice note,Somebody was writing about immigrants,and my cousin introduced him and this story was written.Hope all is well.Thanks again

What a treat to read this!

A nice reading which traces a long and intimate journey bringing an aura of nostalgia, realism, and pragmatism of Bala and Shusila ji. The author covers the various phases of Bala’s periods in more subtle and chunks of storytelling that perfectly depict the person and their story.

Though it doesn’t bear direct relevance to the story being told is that there is no direct mention of the culinary talent(genius) of Shusilaji.

It is a gutsy thing to move half way round the world with $5 and a suitcase. I was struck by their fearlessness and grace. Also, I am old enough to remember that time period and so I was able to “put myself in the picture” so to speak.

While Bala Iyer credits luck, I can’t help but think that the equanimity, intelligence, and confidence of the man had a tremendous impact on his outcomes.

I am so delighted to know Bala and Sushila, and in reading this historical account of their early years I was very touched.

Hello Sheilah, it was so nice to read your comments.Thanks for your note.I always want to know how you are doing.Alexandra said you were not doing too well.Sorry to hear that.Please do take care of yourself, We all love you.sushila

I enjoyed reading about my great-uncle’s life, and I can see a lot of my genes in his old pictures.

Hello Rachel

Nice to read your note.Glad, you can see your genes in your great uncle.Congratulation on your beautiful new home .Good luck on that and enjoy your beautiful kids

If Bala had come to the US 20 years later, he would have definitely become the CEO of IBM in his career. He is a self-made man; not just a theoretical engineer but extremely good with his hands and can fix things. Sushila is a woman of small stature physically, but she is a giant when it comes to running the house and raising the family.. A huge part of Bala’s success is Sushila as she enabled him to focus 100% on his work. Bala and Sushila welcomed me when I came to the US in 1984 and my wife Uma when she joined me in 1987. They have guided us in so many ways that we are deeply indebted to them. Bala has been my Mentor from 1984 and to this day when I need advice, he is the first one I call. Uma and I have been incredibly fortunate to have them in our lives.

Sriram, you have said a lot more than we deserve.It is so mutual..

We have enjoyed each other’s company for so long, our values rub on each other.Thanks for everything

We’ve heard my brother in law time and again relate his stories of the past and his coming to the US with only $5…..but, it is remarkable to see it all laid out with details that speak to his remarkable intellect and confidence. A cheerful, upbeat, and humorous optimist who’s been a source of support and inspiration to many, my husband Raj and I salute, both him and my sister, Sushila for their passion, intensity and continued involvement with the Bay Area Indian community!

This is such an insightful story. Loved it Athai & Athim!

Bala and Sushila. What a beautiful history! I have known you for 46 years and was never aware of much of this! It is inspiring to read such immigrant stories especially for fellow immigrants. Thank you for sharing!

Raja

Comments are closed.