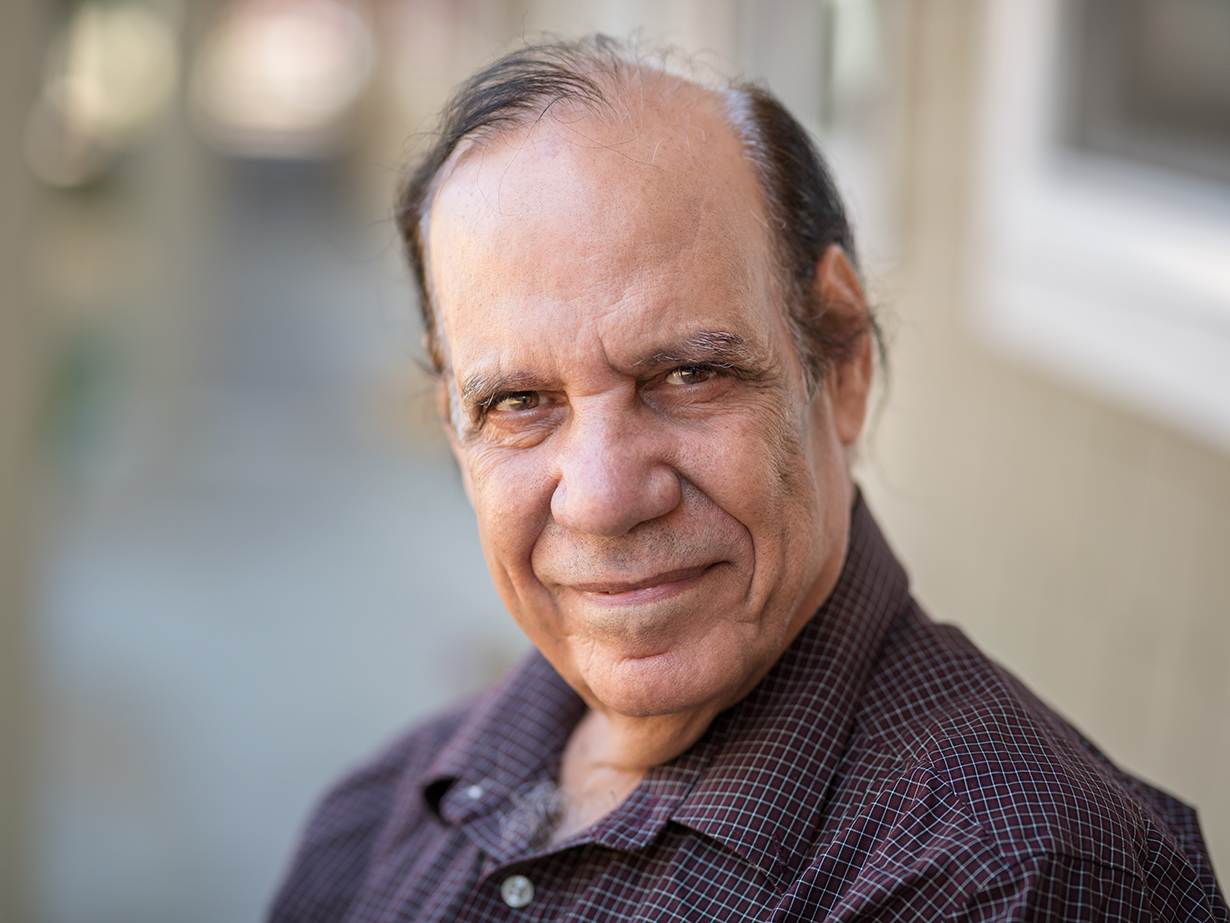

Even in primary school, Farooq Hassan remembers, “I would copy pictures of cartoons or pictures of kings and presidents of that time.” At age 8, Hassan could never have predicted how powerfully the subjects of his early artistic endeavors would influence his future career as an artist.

When Hassan was born in Basra, Iraq, in 1939, the city was a bastion of economic and political stability. In fact, Hassan said, in his childhood years Basra was “much like how America is now” in terms of diversity. The spectrum of cultures and religions found in the city undoubtedly shaped Hassan’s view that “everybody has an idea in his life… and I am free and let people be free.”

In 1958, Hassan left the comfort and familiarity of Basra to study art in Baghdad. He earned his degree, then returned to his hometown to teach art at a primary school. This is when Hassan met the love of his life—an artist and teacher named Haifa Al Habeeb who has been his wife of 50 years. It may be because Haifa Al Habeeb, breaking convention, “tried to ask me to marry her” that the romance worked out so well. “I liked that,” Hassan said proudly.

By the 1980’s, Iran and Iraq were engaged in what Hassan calls, “the dirty war.” To avoid conflict, Hassan was forced to move between Baghdad and Basra. But the moves back and forth made it difficult for Hassan to focus on his art.Yet even in the face of political conflict, Hassan’s life was not without creativity. Hassan had a job designing stamps for the Iraqi government while struggling to sell his own art on the side. Since the stamps often portrayed past and present leaders of the country, the kings and presidents that he had sketched as a child continued to shape the contours of Hassan’s life.

He continued to amass admirers of his work. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Hassan had his art exhibited in Basra, Jordan, Baghdad and London. Sadly, when war broke out again in 2003, Hassan lost some of his most prized work in the looting of the Iraq Museum. During the outbreak of the conflict, Hassan and his family had to escape from Baghdad for two weeks until Saddam Hussein‘s government fell and it was safe to return to Basra. Although the brutal reign had come to an end, Iraq was not free from malicious rule. Two years later, Islamic terrorist groups took control of Basra, which Hassan says “destroyed everything.”

With life so uncertain in Iraq, their daughter, Dalia Altameemi, encouraged them to consider a move to the United States. There, Dalia promised, they would find greater security and freedom. Dalia had served as a field reporter for The Washington Post and as an interpreter for the U.S government in Iraq and was granted asylum to the United States. After seeing how the conditions in Iraq first contrasted with her new life in the United States, Dalia helped her parents apply for refugee status.

In 2010, Hassan and Haifa relocated to Portland to be with their daughter. For Hassan, this transition was not easy. He had to leave all his artwork in the hands of his brother, who opted to stay in Basra. An artist of reputation in Iraq, Hassan found himself in a new country where he had to reconstruct the artistic career he had built over 50 years.

Today, Hassan’s paintings are focused on the female body, a choice which he reflects, “give[s] me kind of a freedom in expressing myself because women are a symbol of life, love, birth and everything in life.”

Having faced his share of obstacles throughout his life, Hassan did not let his new circumstances prevent him from doing what he loves. He uses the kitchen of their modest, two-bedroom apartment–a cramped workspace, to be sure–as his studio. And now he must build a new network using a language he did not grow up speaking and in a culture that, for seventy years of his life, he hadn’t been exposed to.

Despite these challenges, Hassan has been slowly establishing himself as an artist in the Pacific Northwest. His work has recently been featured in galleries and art shows, including at Portland’s Geezer Gallery.

With a lifetime balancing the creation of art amid political upheavals, Hassan says, “In this day we don’t need war when you have the mind to create.”