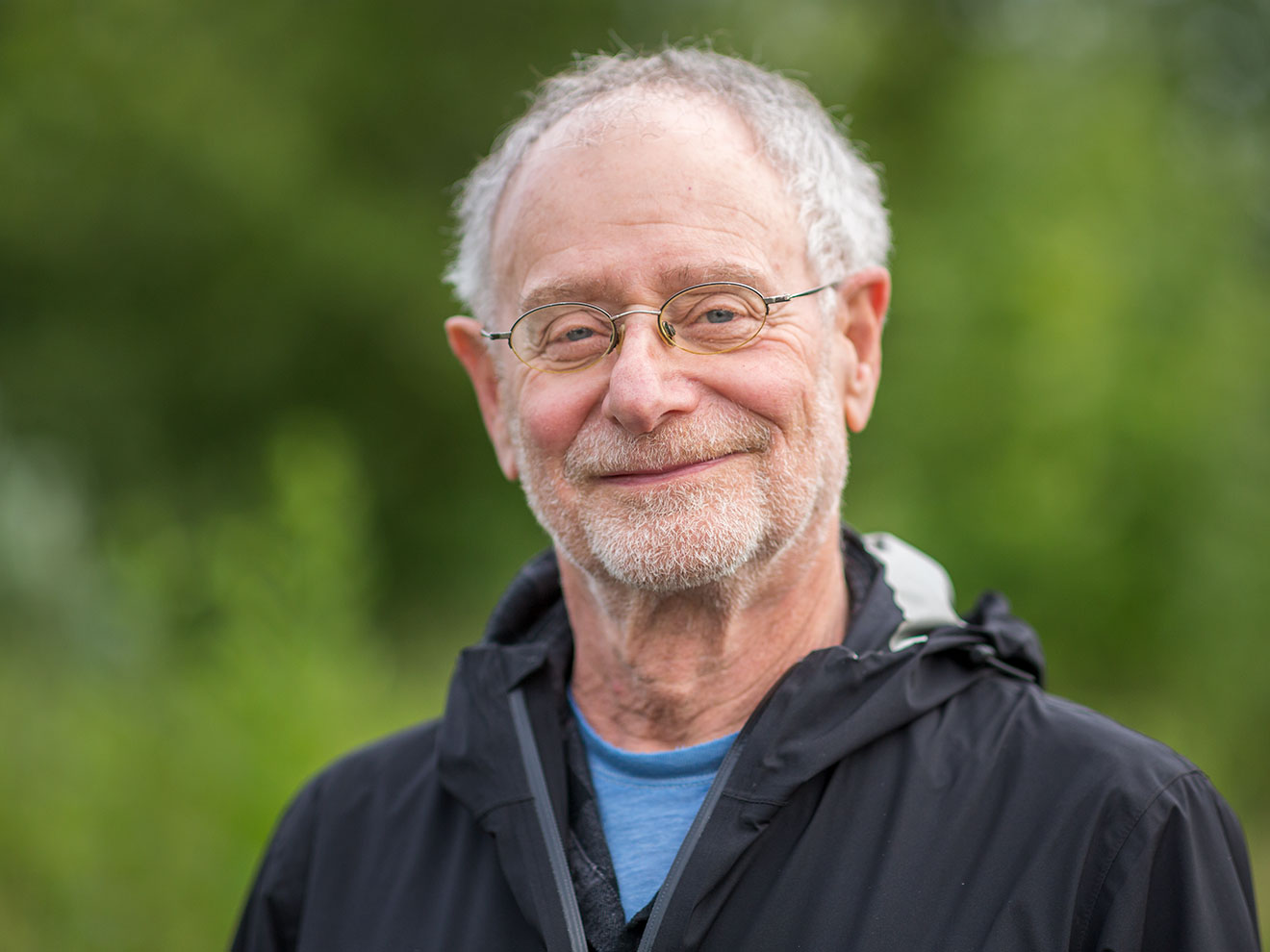

Jack Boas counts his career as historian as beginning at conception.

“Or maybe even before,” he suggests. “I could not avoid it, as a child of the Holocaust, so I made it my life’s work to examine what lessons history can teach us.”

Jacob (Jack) Boas was born in 1943 in the Netherlands, in Westerbork transit camp, the same camp where Anne Frank was kept on her way to the death camp where she eventually died.

Although almost everyone from the transit camp was deported to death camps, the Boas family, through what Boas describes as a series of lucky events, spent two years in transit camps and survived the war.

Boas himself was one of the first pieces of luck for the family. When his parents and their first son, Boas’ older brother, were taken from their apartment in Amsterdam to the camp in February 1943, his mother was newly pregnant. Because women in an advanced stage of pregnancy were not sent to death camps, the couple found a Jewish doctor who testified that his mother was in her third trimester of pregnancy and the family was able to postpone transfer to the death camp based on the doctor’s testimony.

While they were awaiting the baby’s birth, Boas’ father was asked to work in the Hague, the Nazi headquarters during the occupation, as a tailor. Boas’ mother, left behind in the transit camp, watched as one after another of their extended family members, including small children, were sent on the daily trains to the death camps. Her husband was only allowed to visit occasionally but, because his job was valuable to the Nazis, the family was not sent to a death camp. Eventually they were transferred to another transit camp with slightly better conditions.

After the war, in June 1945, the family returned to the Amsterdam neighborhood where they had formerly lived. His parents and a friend opened a tailor shop specializing in men’s suits.

Boas was one of only a few Jewish children in his school.

“There was still anti-Semitism in Amsterdam,” he remembers. “There was just one other Jewish family on the street. People would call me names. But I made friends and played soccer with neighbor kids.”

As a child, Boas knew something terrible had happened, but his parents and their friends did not talk about it.

“They would say, ‘someone did not return,’” Boas says, “And I knew that was code for ‘that person was killed.’”

In 1956, when Boas was 13, the family emigrated to Montreal, Canada, alarmed by renewed threats of war due to international tensions over the Suez Canal.

“My parents could not face going through another war,” Boas says. “They worried that my brother and I would be drafted. Canada had no draft, was easier to get into than the U.S. and was less involved in the Cold War politics.”

His father got a job in a department store selling men’s clothing and his mother worked at the same store, wrapping packages. For Boas, the change was difficult at first, as he missed his friends and had to learn a new language.

His parents found friends in the large Jewish community in Montreal, mostly among the other Dutch Jews there. However, he points out that survivors did not talk about the war till much later, noting that they had to process what had happened.

“My parents did not talk about what happened,” he says. “However, the Germans kept records of everything they took, and my parents applied for reimbursement for all their furniture and possessions that Germans took out of their apartment. There was an elaborate formula of what everything was worth.”

Boas attended McGill University in Montreal for his bachelor’s degree in history, taught high school for several years and then got a Ph.D. in history at the University of California, Riverside. By then, research was being done on the Holocaust, and he wrote his thesis on German ideas of self-perception from 1933 to 1937.

“Not everyone supported Hitler,” he notes. “He had a plurality, not a majority of the votes, but was appointed chancellor because of the plurality.“

After college, Boas worked at the Jewish Family and Children’s Services Holocaust Center in San Francisco and in 1996 came to Oregon to be head of the Oregon Holocaust Research Center, which later merged with the Oregon Jewish Museum.

Boas moved on to teach at Portland Community College and Linfield University in McMinnville, Oregon, and has written five books and a play about the Holocaust, with one more book forthcoming in 2023.

History continues to reveal events from Boas’ own past, including what he learned on a recent trip back to Amsterdam — “a city I still love,” he says.

“For instance,” Boas says, “nobody ever talked about how, during the war, 200 children were taken from my school — the same school I later attended in Amsterdam after the war. I just found this out in 2019 when I visited and, for the first time, saw a plaque at that school about the 200 children who had attended that school just a few years before me. So even now I am just learning about things that happened that I did not know before.“

“There are so many pressures on us to give in to popular ideas, even ideas such as putting Holocaust survivors on a pedestal,” says Boas. “But to me, the message of the Holocaust is that wherever you find injustice, you have to stand up. We have to keep our ability to think. So much comes at us and we have to be able to unravel it. Never think, ‘It can’t happen here.’”